The howl of a coyote in a moonlit canyon. A mountain lion walking silently across a snow field. A black bear foraging with her cubs. A bobcat readying to pounce on an unsuspecting mouse. These large mammals are icons of California’s landscape, and they drive the health and stability of our region’s ecosystems.

Today, these “megafauna” struggle to survive amidst encroaching development and an expanding human population. They’re forced to navigate a complex web of freeways, urban areas, and other barriers while they search for food, raise their young, and live as enduring symbols of the wilderness.

Our Room to Roam project aims to protect these majestic creatures. We work with landowners to reduce human-wildlife conflicts and educate the public about how to coexist with our native wildlife. We monitor the policies and activities of state and federal agencies to ensure these animals are not needlessly killed. And we protect migration corridors by keeping them free of development, reporting road kill from vehicle collisions, and promoting wildlife crossings to give animals the freedom to roam.

Learning to Coexist With Wildlife

The decisions we make as landowners can often mean life or death for our region’s wildlife. Luckily, there are simple steps that we can take to reduce potential conflicts with wildlife. By learning to coexist with nature, we can protect our property, pets, and livestock while ensuring the long-term survival of animals in the wild.

Unfortunately, state and federal wildlife agents often rely on scientifically indefensible and unethical methods to control wildlife populations, like traps, cyanide devices, and the issuance of depredation permits that authorize the shooting of animals. Since the year 2000, the State of California has authorized the killing of 129 mountain lions and dozens of black bears in the tri-county region (Santa Barbara, Ventura, and San Luis Obispo). These “depredation permits” are issued when animals threaten or destroy property, pets, or livestock.

We are working with scientists, wildlife officials, and landowners to reduce the number of animals that are killed each year. We are also analyzing data to determine where human-wildlife conflicts are most common and working with stakeholders to use non-lethal solutions. By learning new ways to coexist with wildlife, we can protect our livelihood while ensuring the survival of these majestic creatures.

Demanding Accountability From Wildlife Agencies

We always hope that state and federal agencies manage our region’s wildlife using sound science, free from bias and political influence. But this standard is not always met, and that’s when we step in to demand accountability.

For example, in 2009, state wildlife officials announced a controversial proposal to open a first-ever bear hunting season in San Luis Obispo County. The officials sought to approve the hunt without first conducting a scientifically-sound population count to determine whether the hunt could be biologically sustainable. Due to overwhelming public pressure, the hunt was postponed, giving officials time to conduct a multi-year population count. Biologists eventually determined that 90% fewer bears lived in the county than previously thought. Such a small population could not sustain a hunt, and the proposal was eventually cancelled.

Our work ensures that the best decisions are made for our region’s wildlife. Their survival depends on it.

Giving Animals Room to Roam

These animals require large chunks of habitat to survive. They also need to be able to move between core habitat areas—when populations become isolated, they are susceptible to inbreeding and a reduction in genetic diversity.

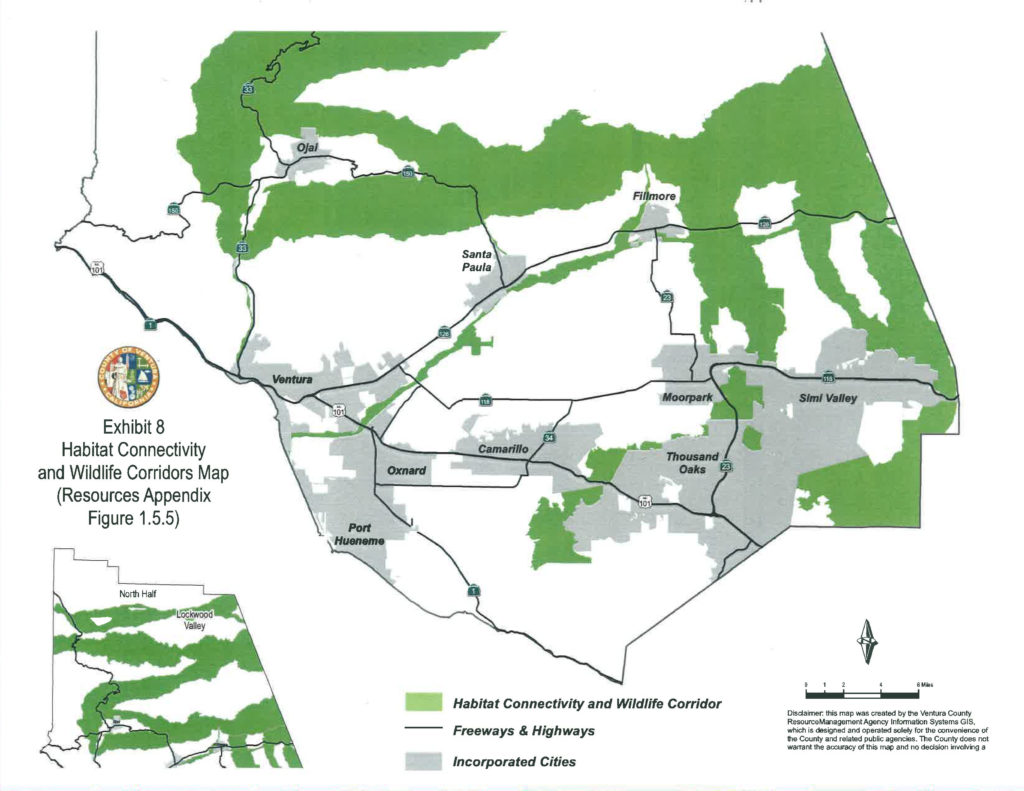

But these large habitats and movement corridors have become fragmented by urban and agricultural development. Massive freeways cut through some of the best remaining habitat, leaving animals with no choice but to travel across them, placing their lives—and the safety of drivers—on the line. Fencing, bright lights, and other barriers make it increasingly difficult for animals to move across the landscape.

Wildlife and transportation officials are beginning to explore the viability of constructing wildlife bridges (or tunnels) where animals most frequently cross highways. In addition, counties and cities are beginning to adopt comprehensive land use policies that strengthen protections for the pathways used by wildlife. In 2019, Ventura County adopted the first-ever wildlife corridor ordinance that will serve as a model for other areas.

We are studying wildlife mortality data for the highways in and around the Los Padres National Forest (Interstate 5 and Highways 101, 33, 150, 166, 58, 46, and 1). We are working to improve the ways that state transportation agencies record wildlife mortality data. And we are encouraging drivers to submit their roadkill observations to an innovative statewide database managed by UC Davis. Improving data collection is the first step towards finding solutions that will allow wildlife to roam freely across the landscape.

Support Our Room to Roam Fund

Our region’s iconic animals need your help. Every day, their survival is challenged by a confusing network of roads, fences, bright lights, and urban sprawl. Donate today to help us ensure that there are strong programs in place to secure a safe future for wildlife in and around the Los Padres National Forest. When we protect the wild, we protect ourselves.